Sailing alone: the cultural sector of Jordan in times of Covid-19

Door Mariam Shahin, op Fri Aug 07 2020 16:27:00 GMT+0000Coinciding a nationwide lockdown to halt the spread of Covid-19 in Jordan, the country’s government introduced martial law. The national cultural sector was left without targeted assistance of any kind. How will the cultural field in Jordan survive?

On 20 March 2020, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, a country with a population of ten million people and approximately 3 million registered refugees, went into a nationwide lockdown. A lack of urban decentralization and a pressing issue of overcrowding in refugee camps and in the main cities has been challenging to control the Covid-19 outbreak. With an economy based on four major sectors (general industries, banking and finances, transportation and telecom, and tourism), the government had to ward off a crisis after the lockdown put all economic activities on freeze until the end of May 2020. Was there any space left to protect the cultural sector?

A changing Jordan

What sets apart Jordan from other countries and creates a more complex ground for emergency policies related to the Covid-19 outbreak, is undoubtedly the presence of many refugees from the bordering countries of Iraq, Palestina, Saudi Arabia and Syria. Jordan is a popular destination for migration, because the nation remains one of the few politically stable countries in the Arab world. Syrian refugees in particular represent close to 10% of the population and still live in severely overcrowded refugee camps. Overcrowding also exists in cities, such as the capital city Amman and the second biggest city Zarka, where less recently displaced refugee groups are located.

The Jordanian government followed the recommendations of the World Health Organization and implemented a series of control strategies on both local and national levels in order to limit the spread of Covid-19. Moreover, Jordan has made medical treatment for Covid-19 available to all those living and residing in the country. This is an exception compared to other countries. Saudi Arabia, for instance, only gives medical treatment to its own nationals, simply shrubbing off unregistered people with a ‘stay at home’-warning. Still, something particular happened on the 20th of March: the government introduced martial law. This law can only be inserted in the case of a severe national crisis or emergency, and grants military control over regular civil functions in society.

However, not every result of this system of control has been nefarious.

This context gave way to attack political critics of the current government. Many overt critical voices have been questioned and remain in custody. Additional concerns arose among the population about their corporate and private assets. Under martial law, the government has the right to freeze bank accounts of all citizens, as was done in Lebanon earlier in 2020. However, not every result of this system of control has been nefarious. For instance, the government could freely prevent employers from firing their employees. Many companies were relieved of paying the rent of their office buildings in the absence of their use. All loan repayments have been frozen for three months and interest rates for new loans have been lowered.

At the end of May, some lockdown measures have been eased and so-called ‘soft loans’ - small loans with interest rates of 2% - were made available to companies of all sizes and industries. Specific areas and parts of the population (travelers, drivers, pilots, etc.) were quarantined separately in government-paid hotels. Working class travelers were lodged in less comfortable types of housing.

Free-launching culture

Jordan has a major artistic and cultural sector, with more than thirty art galleries, ten theatre institutions and more than twenty concert halls, topped with numerous private and public or non-profit arts institutions. The cinema and television industries play an important role in the country: more than thirty productions were created in Jordan in 2019 only. The entire cultural sector provides an income to up to 25.000 artists in various disciplines. However, there were no emergency funds cleared for the cultural sector and most of them fell outside possible economic safety nets during the lockdown and have been struggling to rekindle their income since the economy at large shrunk almost overnight. Most cultural workers and artists do not have access to social security or contract jobs in a gig economy. Mostly self-employed freelancers, they also don’t have medical health insurance. Luckily, Covid-19 and cancer treatments are free for everyone in Jordan.

Concerning structural and financial support, the cultural sector was left without targeted assistance of any kind.

The cultural sector was left without targeted assistance of any kind during the pandemic crisis. Most artists and cultural workers in any field do not have job security. The majority of these professionals are not union members and thus have no organized voice to protect and lobby for their social security and their work rights in government. There are some unions in Jordan that could protect the cultural sector in particular. High annual fees, however, hold back many professionals to join.

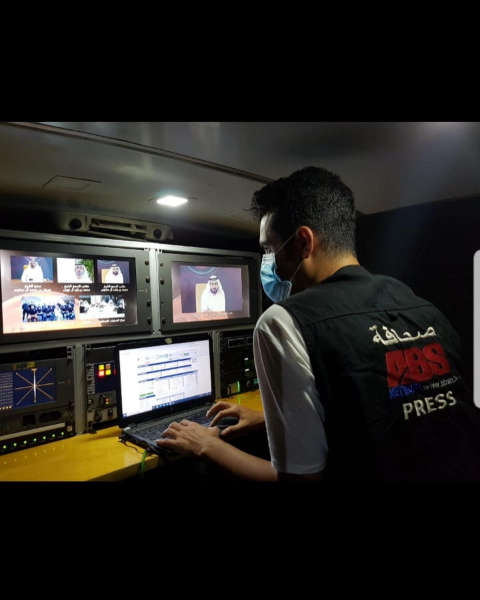

The film and television sector, which creates national and international productions, is mainly staffed by freelance producers and media workers. With a small exception of the staff of a recent Netflix production, none of the staff of nearly twenty other productions planned for 2020 were paid during the lockdown period. The independent documentary sector fared a little better: some editors found the time and space to finalize some previously shot productions. ‘I spent the two months [of lockdown] editing several episodes of a documentary series for the Al Jazeera Channel,’ said editor Saed Aruri. Another editor and colorist, Eyad Hamam, spent most of the lockdown in his home office coloring a drama film he had edited.

In the meantime, many other professionals were unemployed throughout the lockdown period.

Nevertheless, other staff, such as camera operators, directors or producers who were not employed by larger production companies did not receive filming permits and thus could not continue any work during lockdown. Large companies with employees, however, received accreditation to work during lockdown from the government. By all means, they reasoned that only workers with social security and medical coverage, two things large for-profit companies are obliged to provide to their workers, should risk being exposed to the virus. Other freelancers have been excluded from gigs by international agencies in Jordan, also due to safety concerns. Many photographers were able to skirt filming permits and record empty streets, residents waving at their windows or socially distanced shoppers in front of supermarkets.

In the meantime, theatre producers, make-up artists, costume designers, actors, and many other professionals were left unemployed throughout the lockdown period. The in-house workers of theatre institutions and concert halls had a little more luck: the government rented the halls as temporary lodgings for traveling truck drivers, taxi drivers and other types of international workers. With the rental fees paid by the government, the institutions paid their in-house staff.

Saving the arts on the web

The fine arts sector had to close shop during the lockdown too. Most artists received no income during the lockdown. Only after the easing of the strict measures at the end of May, artists, galleries and institutions organized online exhibitions and auctions. Mona Deeb, curator at Nabad Gallery in Amman, worried about paying the rent of her gallery space. ‘We are going online with an exhibition, just so we will be able to pay the yearly rent in August. Otherwise we will need to move out of our exhibition space.’

I had to walk five kilometers to the local FedEx office, because of the ban on all travel by car.

Curator Leila Masri, in the meantime, kept in touch with her clients via social media. ‘No one bought anything, but it was a way to keep the work alive - keep [people] looking, garner [their] interest.’ One of the few artists who sold something was Iraqi painter Shaker Al Alousi. ‘In early April a Saudi Arabian woman contacted me. She had seen a painting on my Facebook page that she wanted to buy. She insisted that I find a way to send it to her and she paid by Western Union Transfer. I had to walk five kilometers to the local FedEx office, because of the ban on all travel by car. In the end she got her painting and I got my money.’

Not only the visual art galleries decided to make a digital turn, also the music and film industries realized they had to use online platforms and social media to haul attention and raise a public. Jordan’s Royal Film Institute, for instance, provided free film screenings online. A vast array of other cultural platforms provided free concerts throughout the lockdown period. Ilham Al Madfai, a famous Iraqi singer based in Jordan, aired a live solo concert online to his fans for free. The concert reached four million viewers across the Arab world. In terms of actual income, the lockdown months obviously were no fertile ground. ‘It will be a long time before we have paying viewers or concertgoers again. Perhaps they will buy some music online, but Covid-19 hit our industry really bad,’ said Al Madfai.

Governmental response to the cultural crisis

The government of Jordan did not provide any possible relief funds to support and save the arts and culture of its country. Most effort was seen by Jordan’s Ministry of Culture, who launched several specific competitions with small fees for the winners. These competitions were mostly directed towards youth or very young cultural makers. For instance, the Ministry launched an online competition for poetry and short stories written by children and young people between the age of 10 and 25. The competition was launched through their social media platforms. The winners got a chance at a money prize of 1000 euros, while at the same time professional literary authors were stunned at home without any earnings or security.

Somewhere between support, talent scouting, and youth work, the government’s efforts were minimal and completely ignored the professionals in the sector.

Similarly, the Ministry launched a short film competition for young people between the age of 15 and 25, based on public voting. They created an online event with screening of the short films and asked viewers to vote online. The winning short film creator received a money prize of 1000 euros, whereas the runners-up received about 100 euros. The same concept of public voting through an online platform was used for a children’s art competition. The winning kids (or their parents) received cash prizes of about 1000 euro.

A meager attempt to aid visual artists was made by organizing an online exhibition with a public voting system and a 1000 euro prize for the most popular artist. Somewhere between support, talent scouting, and youth work, the government’s efforts were minimal and completely ignored the professionals in the sector.

Speculation and uncertainty

An entire sector is living in uncertainty and precarity.

The cultural sector of Jordan suffered enormous losses. Not only were they unemployed for two and a half months, but even after society started ‘reopening’ after the strict lockdown period, they remained before closed doors. There were no possible gigs or jobs to control the damage done by the crisis. Film productions are said to ‘perhaps’ begin again in August under new safety conditions and regulations. Musical concerts, theatre productions, art exhibitions, poetry readings and other cultural events will not take place any time soon. An entire sector is living in uncertainty and precarity.