The Defutured Soil of Shinkolobwe

Door Toshie Takeuchi, op Mon Jun 02 2025 06:02:00 GMT+0000In een visueel essay onderzoekt filmmaker en kunstenaar Toshie Takeuchi de verbanden tussen de Shinkolobwe-mijn in Oost-Congo en de nucleaire wapenwedloop in de twintigste eeuw. Geconfronteerd met archiefsporen van blokken uranium in de collectie van het AfricaMuseum vraagt ze zich af hoe ze het verhaal van de Congolese mijnwerkers kan vertellen.

When I lived in the Hague, I used to be part of an artists’ community that occupied the abandoned embassy of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The building was occupied from 2010 to 2023.

In the beginning, I didn’t fully understand the space, its context and its history. I had no idea about the Congo – the grotesque colonialism of King Leopold II and the Belgian state, the colony’s longing for independence sabotaged by Belgium’s allies, and the imperial colonial legacies still shaping the country’s present political instability. I didn’t know about the massacres and the displacement of its inhabitants, or about the dispossession of its lands for never-ending mineral exploitations by the Global North.

We were a group of artists from the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Japan, USA, Israel, Poland, Slovakia, and Taiwan. According to an interpretation by our lawyer, diplomatic immunity of the Congo still applied to the premises, so that we were protected from Dutch authorities while we were living there. But as a collective of artists, we never reflected on the ambiguity of the situation. We didn’t speak about the Congo, unless when we discussed our rights of living in the building, or in the context of promoting its identity, as the abandoned former embassy was now also used as a cultural venue for underground music and community dining.

I decided to create a film portraying the embassy and the ambiguous grey zone in which it hosted us. In the process of researching Congolese history and the background of the closure of the embassy, I met a bookshop owner in Matongé quarter in Brussels. This was around the end of 2013. He was about to return to the Congo to run in a local election. He told me that one day he would like to walk from the Congo to Hiroshima to demonstrate for peace and solidarity with the victims of the atomic bombs.

The Aesthetics of Peace

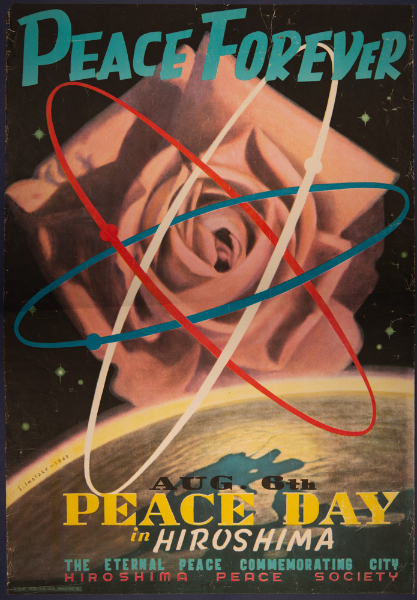

On 6th August 1949, four years after the US government dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, the ‘Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law’ was enacted in US-occupied Japan. On the same day, the Third Hiroshima Peace Festival was held. On the poster for the festival, ‘Peace Forever’ was written on top of the symbol of the atomic nucleus. The propaganda campaign ‘Atoms for Peace’ – the title of a speech delivered by U.S. President Eisenhower at the UN General Assembly in New York in 1953 – strategically separated the public perception of nuclear weapons and of nuclear energy. The US and Japanese leaders were particularly keen on propagating nuclear technology by positioning the survivors of the atomic bomb as its promotors – this despite evidence that they were still suffering daily from the effects of residual radioactivity. On top of that, the survivors were being forced to participate in the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC), a research centre which had been established by the US in Hiroshima and Nagasaki to study the effects of radioactivity on human bodies. ABCC never gave medical treatment to the victims, nor were any study results ever shared with them. Five years later, the government organized the Hiroshima Great Reconstruction Exposition ‘58 (Hiroshima Fukkō Dai Hakurankai ‘58). Even though the victims and citizens were skeptical at first, the expo, which presented nuclear energy as the way towards peace and justice for all of Japan, finally was an enormous success.

There is an apparent modern and colonial duality in the narratives of nuclear history.

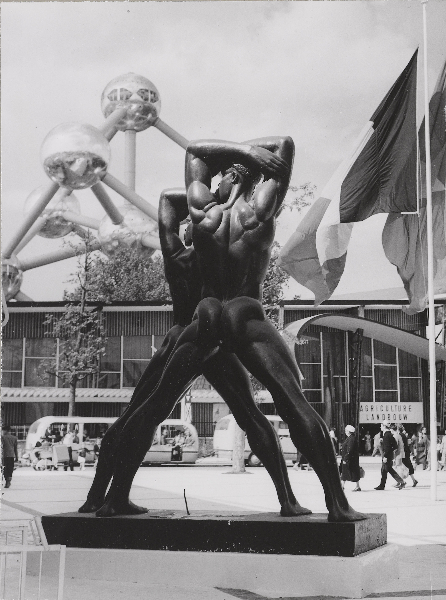

At exactly the same time, in Belgium, the DR Congo came to play both a visible and invisible part in the cultural imagination of the post-war nuclear moment. Strikingly, the archival footage of the ‘Congo Section’ at the Universal Expo 58 in Brussels shows Congolese people in a human zoo alongside the Atomium landmark and the exhibition of uranium ore. But other aspects are kept invisible. Shinkolobwe, a mine in the province of Haut Katanga, DRC, and the main source of uranium ore for the development of the first atomic bombs, was nowhere mentioned; its name was kept secret or even erased from maps at one point. Until today, the history of Shinkolobwe has been largely neglected.

There is an apparent modern and colonial duality in the narratives of nuclear history. While referring to the razed lands of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, decolonial scholar Rolando Vázquez in his paper ‘Precedence, Earth and the Anthropocene’ (2017) explains that modernity’s relentless destructive power (‘defuturing’) lies in reducing time and space to the surface of empty representations: ‘Defuturing expresses the foreclosure of relationality, the loss of relationality as grounding precedence, of space as hosting and enabling and time as the radical multiplicity and potentiality of what has been. The [power of the] chronology of modernity lies in the logic of separation in its severing of our relations, in the emptying of our historical site of experience.’

From that perspective: could ‘soil’ also be regarded as a space of connectedness, as the hosting space of the erased memories, particularly of the Congolese miners in Shinkolobwe, who were forcibly mobilised to dig up the most powerful uranium ore, without any knowledge about its usage for the instant mass-wiping of human lives?

The History of Erasure

Belgian company Union Minière du Haut-Katanga (UMHK) started its industrial mining at Shinkolobwe in 1921 to extract radium, a rare, expensive mineral used in medical science, in cancer treatment, and in self-luminous paint for clock dials. For decades, the company dominated the world market of radium, but when it came to uranium, its use was limited. Until the outbreak of WWII: in 1939, scientific research to build atomic weapons became urgent. Union Minière was ‘perfectly prepared’ for this situation, as it could supply the sudden demand for uranium ore, as Luc Barbé writes in La Belgique et la bombe (2012).

During at least the first ten years of the Cold War, Belgian Congo was the main source of uranium for the development of the entire Western nuclear industry.

As part of the US government-led Manhattan Project, the uranium trade between the US and Belgium was conducted through secret bank accounts. Neither the production of the bomb nor the source of the material was known to anyone other than a few top officials. On 7 August 1945, Winston Churchill deliberately thanked only Canada for its contribution in uranium, diverting attention from the role played by Belgian Congo.

According to Barbé, Congolese uranium was used not only for engineering the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II. During at least the first ten years of the Cold War, Belgian Congo was the main source of uranium for the development of the entire Western nuclear industry. Several thousands of tons of uranium ore from Shinkolobwe were sold to the US. To make sure that none of the ore fell into the hands of the Soviet Union, the name of Shinkolobwe was kept from the news.

In 1959, one year before Congo’s independence, New York businessmen asked Patrice Lumumba if the US could keep its steady access to uranium like before. Lumumba answered clearly: ‘Belgium doesn’t produce uranium … in the future, if the Congo and the United States could make their own agreement, it would be to both our advantage’ (quoted in Susan Williams, Spies in the Congo, 2016).

In 1960, Lumumba, fighting for national unity and for the liberation of the Congo from the colonial ties and the mechanisms of exploitation, was elected the first democratic Prime Minister of the newly independent Republic of the Congo. Right before Congo’s independence, Union Minière sealed off the Shinkolobwe mine with concrete. Only six months after the independence, in the midst of political turmoil caused by the recalcitrant colonial powers and heightened by Cold War tensions, Lumumba was assassinated by Katanga secessionist leaders, with help of Belgian officers in a coup led by the US.

Invisible Archives

The labour conditions and health consequences of working in the Shinkolobwe mine have been largely ignored. In the 1920s, when Union Minière mined the soil for radium, they sorted and transported high-quality ore to refining facilities in Olen, in Belgium. The vast amount of the highly radioactive ore bearing uranium was discarded and piled into massive waste heaps at the site. It most likely contaminated the entire area – soil, water and air.

During the Manhattan Project, Congolese miners were forced to work day and night in the Shinkolobwe mine’s open pit. They sorted and packed the uranium ore by hand and sent hundreds of tonnes to the US every month. Susan Williams writes that ‘according to estimates, they could have been exposed to a year’s worth of radiation in about two weeks … [and] many of the miners’ homes were constructed from radioactive materials.’ In fact, in the colonial archives of AfricaMuseum Tervuren, there are photographs that show the miners at Shinkolobwe working with bare hands and feet. Some of them appear to be children.

Diseases related to radioactive material were already identified in the 1920s in the US and Czechoslovakia. Union Minière, however, seems to have ignored this; none of the effects of radioactivity were documented in the company archives.

The uranium block, once exhibited as a beautiful, exotic, and fascinating scientific object, is now stored inside concrete walls, somewhere in the museum basement.

In the 1990s, Prof. Donatien Dibwe dia Mwembu from the Department of Historical Sciences at the University of Lubumbashi sought to investigate the working conditions in the Shinkolobwe mine. He consulted the archives of Gécamines (successor of UMHK), but told me in an interview that he didn’t have access to the archives of Shinkolobwe. Gabrielle Hecht, a scholar working on nuclear history and mine waste in Africa, writes in Being Nuclear (2012) that ‘workers of the Shinkolobwe mine were omitted from the scientific studies on radiation exposure in mining … and the invisibility of their exposure cannot be corrected through archival diligence, because the records – assuming they were even kept – do not appear in the inventory of the Brussels archives.’ According to Dennis Pohl (‘Uranium exposed at Expo 58’, 2021), Union Minière has not yet made its entire archive publicly accessible. The catalogue from the years 1951– 1961 is classified as ‘secret’ until 2050.

Today, Shinkolobwe remains inaccessible. The area is under military control and even local journalists cannot access the site. Daniel Allen of the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS) argues in ‘Uranium Security in the DRC’ (2024) that artisanal mining at the site continues till today. The diggers, depending on mining to make a living, are still believed to be exposed to uranium’s radioactivity, even though they are not necessarily directly mining uranium ore. Both copper and cobalt ores are often mixed with uranium. Satellite maps show that the new industrial mines at both sides of the old Shinkolobwe mine are rapidly expanding.

Autoradiography of Defutured soil

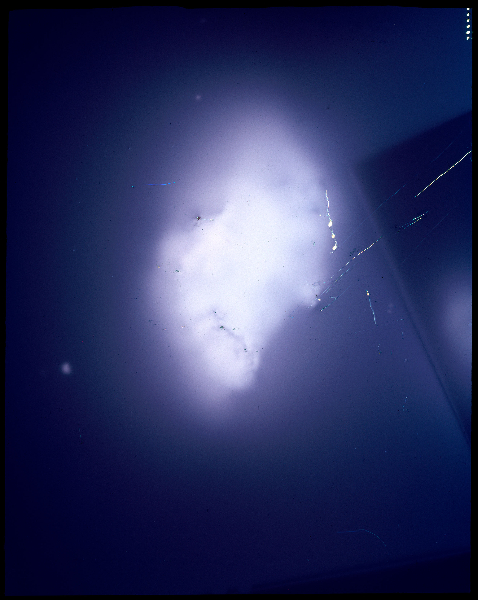

While I was going through the archival photos of Union Minière du Haut-Katanga at the AfricaMuseum Tervuren, my attention was caught by the picture of King Baudouin curiously eyeing a gigantic uranium block. I started thinking that the radioactivity of this particular uranium block could be my starting point to tell the erased stories of the miners at Shinkolobwe. Could I make it visible through an autoradiographic image – a photograph produced by radiation?

That uranium block, once exhibited as a beautiful, exotic, and fascinating scientific object, is now stored inside concrete walls, somewhere in the museum basement. It is not exhibited, but shielded from the public eye, and it is prohibited to take a photograph or to be near it. It emits 2100 µS/h gamma radiation. If I would stand close to it for 30 minutes, I would have been exposed to ‘a year’s worth of radiation’.

I thought of the bare hands of the invisible miners, who dug and carried this block from the mine, to the wagon, to the rail, and how the rock was then probably brought to the scientific laboratory of U.M.H.K. How much radiation did their bodies absorb? The wounds on their hands were probably completely smeared with radioactive dust. Could they at least wash their hands? Did washing hands even make sense if there was only contaminated water? Did it make sense, if they lived in houses built with radioactive material?

At the museum, I was told that there was no inventory of this block of uranium. It seemed that no one knew how and when it was put into their collection. All that was known was that it was dug from the Shinkolobwe mine, like all 1.200 uranium samples in the museum.

This article was published in the context of Come Together, a project funded by the European Union.